Aztec Electric Racing -- First Semester Review

(Summer 2017)

AER (Aztec Electric Racing) is a new FSAE electric team at San Diego State. I initially joined as a fresh transfer student, completely clueless about any single aspect of building a car. After only one year of being in this club, I have been empowered in both design and manufacturing, and look forward to another three semesters of learning and building.

Our first FSAE competition is over, and it is time to look back. This review is less about the specific engineering choices made and more about how the team worked and evolved together. The scope concerns the Tractive and Controls systems -- Anything electrical, as well as the things that "make the car go."

AER spent its first semester in the Bioscience Center at SDSU -- There's nowhere to build a car, but these were great lodgings for our first R&D phase.

- September 2016

-

- Club founded; Author joins up, clueless but ready to learn.

- Team focus: Learn competition rules, and prepare preliminary designs

- Much research occured during this phase, as team knowledge built up from zero. Motors, controllers (motor driver/inverter) and batteries explored.

- Next milestone: Preliminary design review (PDR)

- Preliminary Design Review (PDR)

-

- For AER, PDR is the first 'gate' in our 'phase gate' engineering approach introduced to us by Dr Youssef (our faculty advisor at the time.) At this point, the team captains are expected to have developed high-level goals of what they want to achieve, and these goals trickle down to drive technical development within the functional groups based on business-case justification. Each group from the team (management, as well as each technical area) presents their design concepts along with the alternative options and justification for the proposed option. The team (hopefully) has gathered some SMEs (Subject Matter Experts) who will critique not just the technical aspects of the designs, but also their feasibility within the organization.

- Dr. Youssef pushed our professionalism and presentation skills significantly -- After multiple revisions and the team was satisfied with our presentation (or rather, too tired to iterate further,) Dr. Youssef was still appalled by the quality of our work -- He sets high expectations, and believes all work has room for improvement. Looking back, some of our workmanship was truly "kindergarden" engineering; We were lucky to have our advisor to help us through those times.

- PDR certainly did its job in helping to guide our designs, but didn't help at all with the unknown unknowns. Later during the year, pressed for time, I found myself choosing components and approaching designs in an ad-hoc manner -- I realized that they would benefit significantly from the PDR and CDR treatment, but time never allowed.

- Lasted 8 hours! (And if we had any idea of the scope of the project, could have taken twice as long.)

AER's first-ever PDR kicked off a tradition of tough-love, constructive criticism, and relentlessly progressive standards for engineering work.

- October 2016

-

- Author attempts a wheels-to-motor energy analysis. Many of the individual pieces were there (Modeling of tractive force necessary to overcome resistances) but I never put the resistance model together with the mechanical losses, inertia of rotating parts, to a usable simulation. (An important project I will not give up on -- The ability to estimate the kWh necessary to finish the endurance event would be quite valuable.)

Rereading this 2 years later: Side analysis projects like this were ultimately set aside as less important -- The focus is still on getting the car to drive reliably to finish the endurance race, and optimization analysis projects like this will follow that as-of-2019-imminent success. - Somewhere between September/October, team scrambled to select a motor, believing this to be the basis of all other Tractive decisions. After an hours-long Oggis meeting, we decided on the Astroflight 4345. (Hah, just kidding, within a week we reverted to the Emrax 208, an extremely popular motor within FSAE and lightweight electric applications in general.)

- Unknown unknowns begin to crop up, as we become more familiar with rules and general design requirements. ("Do we even need a Battery Management System?" & Temperature monitoring of cells)

- Author was officially part of the "Tractive System", which was responsible for driveline (gearing, differential, and power transmission) and power generation (motor, high voltage connections, HV battery). I flirted with (surface-level) research into driveline components, differentials, battery charging, motor controllers, and our search through almost every motor known to be on the commercial market (over the next few months.)

- Author attempts a wheels-to-motor energy analysis. Many of the individual pieces were there (Modeling of tractive force necessary to overcome resistances) but I never put the resistance model together with the mechanical losses, inertia of rotating parts, to a usable simulation. (An important project I will not give up on -- The ability to estimate the kWh necessary to finish the endurance event would be quite valuable.)

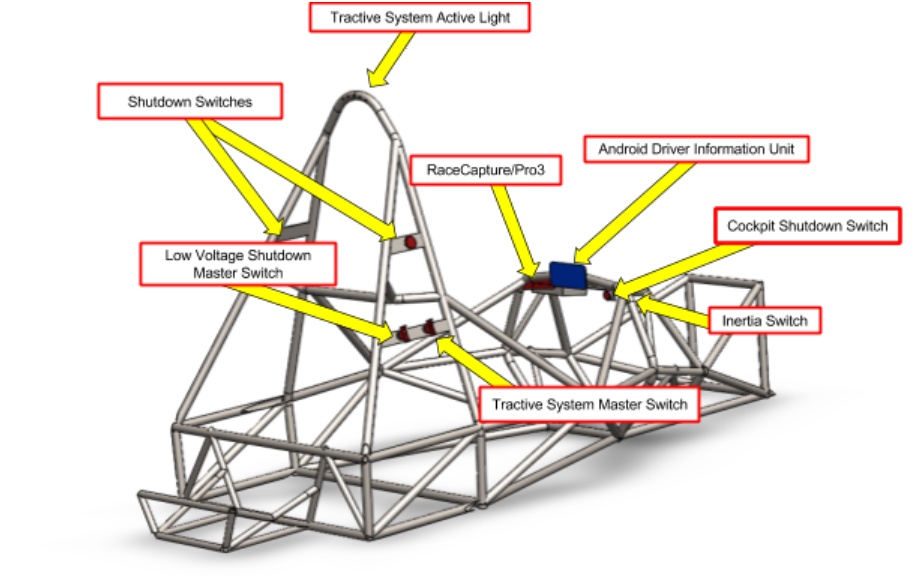

An early concept diagram submitted as part of our Electrical {Safety, Systems} Form (ESF.) The idea of having a smartphone embedded in the steering wheel for instrumentation and readout was deprioritized and never implemented.

Much of the work around 2016-2017 was in finding all of the subsystems, safety features, and interface elements required for a rules-compliant vehicle that could compete in our competition. The team researched each required element and slowly built up a knowledge of solutions available for our engineering problems.

- November 2016

-

- Team begins to move forward with Emrax design implementations. Team leaders begin to become overwhelmed with their share of the work, but delegating design work to someone who has absolutely no domain knowledge is very difficult. (ie, Selecting specific driveline components that satisfy poorly defined constraints when you have to turn to your teammate and ask "what exactly is a bearing?")

- I experienced this same problem from the other side later during the semester, when the details and domain knowledge of the safety circuits and devices, and how they interrelate, existed primarily in my head. I still have not figured out how to bring someone up to speed quickly, when I spent months researching the background and implementation details.

- Although frustrating, this allowed for the less experienced team members to get some experience putting a mechanical system together, learn to read drawings, communicate with companies to get information, and shop for components.

- Documentation rears its ugly head: Design reports (Failure Modes Analysis, and the Electrical Safety Form) initial submissions are due near the end of the first semester. Our initial attempts to fill out these documents were rather misguided, as we made efforts to fill out every section regardless of whether or not it was bullshit.

- As a FSAE alumni explained to us, when you cannot detect or handle a failure in an FMEA, you simply leave the box blank. The risk score blows up, and is easily flagged for redesign.

- The ESF was initially 'fluffed up' which not only missed the point of the document, but takes up valuable space in the maximum 100-page document. With datasheets for every electrical component in the system (as the judges expect) and every section filled out, space becomes a premium.

- Team begins to move forward with Emrax design implementations. Team leaders begin to become overwhelmed with their share of the work, but delegating design work to someone who has absolutely no domain knowledge is very difficult. (ie, Selecting specific driveline components that satisfy poorly defined constraints when you have to turn to your teammate and ask "what exactly is a bearing?")

- Critical Design Review

-

- As the pinnacle of our initial designs, the CDR featured first attempts at a motor + driveline package, and an accumulator with cooling. The Emrax motor, a Chinese pouch cell, and Bamocar controller were analyzed for weight, power and cooling.

- Our Tractive system had only worked on these few components in detail, although we had iterated on them a few times. This left many of the aforementioned unknown unknowns. (You're probably tired of reading that tired phrase, but it was a huge problem for our team.)

- Controls team had concepts for the circuits which may or may not have worked, but they never picked component values, desk-checked that the circuits worked, or built/bench tested the circuits.

- Many electrical safety components were passed back and forth between Tractive and Controls (BMS, precharge/discharge, contactor-driving safety circuit) for months because nobody knew what they even were, or what work they entailed.

- The majority of our members came from the existing combustion, bringing considerable knowledge regarding all of the mechanical systems on the vehicle. We really did not grasp exactly what was required for the electrical systems, and didn't have much of an idea of the quality of work expected by the judges. This contributed to the stagnation of the controls system.

- Safety circuit concept existed and had been analyzed, but the Controls captain left little to no instruction on how to carry on his work. (Work mostly had to be scrapped and redone.)

- Torque vectoring and regenerative braking were analyzed before the basics had been completed, spreading controls further. These projects are interesting but entirely unnecessary for a working vehicle, and were de-prioritized.

- December 2016

-

- Surprise! Club receives none of the expected funding from the school, and begins to evaluate alternative designs for the Tractive system. (Our initial modus operandi assumed whatever funding we required, an ambitious promise from our president. -- Baja got all the money, and both Formula teams were left with nothing.)

- As with every other setback our team worked through, this was frustrating but ultimately a *good thing.* Our dream design, with the Emrax motor and the worlds most perfect battery cells, was put on the chopping block. We were instead forced to consider cost/power/weight tradeoffs.